Introduction

The widespread nature of pain (in all its form) and the devastating impact on individuals and their families has been recognised in the United Kingdom (UK). One recent example published by Health Survey England (1) showed that 31% men and 37% women experienced chronic pain. Pain education for nurses and healthcare professionals is a seen as an essential part of the solution to this and has been a key recommendation of several national reports from organisations such as the Royal College of Nursing (2), the British Pain Society (3) and patient groups such as the Patient’s Association (4). One of the most influential reports was published by the Chief Medical Officer in 2009(5). Reviewing the impact and services for chronic pain, the first of eight recommendations was that pain should be included in the curricula of all healthcare professionals.

Comprehensive and effective pain education is vital in order to tackle the growing problem of pain and its impact. Having recognised the problem of pain and the importance of pain education in the UK, critically reviewing the nature and provision of this education is the next step in order to identify strengths and next steps for improvement. This article discusses the pain education for nurses in the the UK highlighting the current systems for pre-registration and postgraduate (post-registration) study and exciting new developments that will drive changes to enhance pain education.

Pre-registration education

University-based programmes of study prepare nurses for registration with Nursing and Midwifery Council (NMC), the body that sets standards and regulates these professions. he programmes are delivered at Bachelor degree level (3 years) or Master’s degree level (2 or 3 years) giving students a minimum of 4,600 hours of study equally split with 50% practice and 50% academic study. Nursing students pursue one particular specialist area of nursing known as a field of practice. Students can choose a university programme that focuses on one particular field – adult nursing, children’s nursing, learning disabilities nursing or mental health nursing.

The NMC (6) defines the standards for pre-registration programmes, criteria that need to be met for each programme before it is approved to run. Universities use this framework as a basis for their own curriculum design. The pain content of the NMC’s (2010) document, the Standards for Proficiency for Pre-registration Nurse Education, is minimal. The document refers to managing the complex needs of individuals around symptom management including pain but does not contain further detail. It is up to individual universities to translate this into a curriculum and timetabled learning for students.

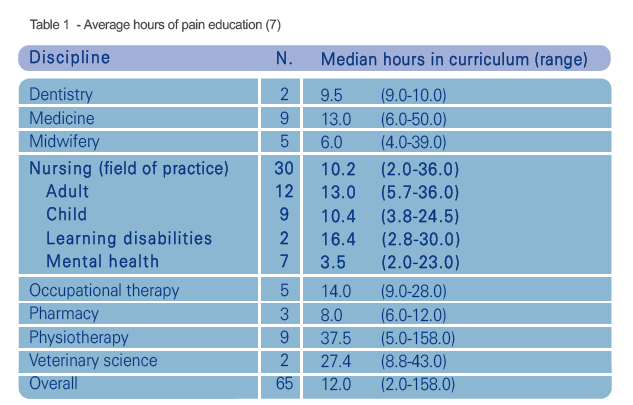

As a consequence of this limited detail in the national standards, there are large variations in the amount and types of pain-related education pre-registration nurses receive. This was demonstrated in a survey of 19 universities who were delivering 105 programmes of study to a range of professionals (7). Table 1 highlights the low number of hours nurses and other disciplines received with nurses averaging 10.2 hours (range 2.0-36 hours) across the 4,600 hours curriculum. This suggests that pain is given a low priority in terms of teaching and learning content.

The type of teaching and learning is also important; the Briggs et al (7) survey revealed that students receive predominantly lecture and case studies to drive learning which is often assessed through exams. These techniques can be useful learning tools but they encourage transmission style of teaching that promotes surface learning and knowledge recall (8). A variety of learning approaches are needed to promote a deeper learning in order to develop the variety of skills needed to manage pain in clinical practice; communication skills, empathy, assessment, problem solving, decision making and evaluation. Education should focus on more than increasing knowledge and should include improving attitudes and skills, respectfully challenging misconceptions and ensuring clinical competence.

Managing pain effectively is an interprofessional activity; it requires a team approach with the patient at the centre. In the UK, there has been a general drive for students to have interprofessional education (IPE) as part of their curriculum. The Centre for Advancement of Interprofessional Education (9) defined IPE as ‘learning where students come together to learn with, from and about each other’. This type of education has been shown to improve collaboration and interprofessional communication (10), essential skills for pain management. The Briggs et al (7) found no examples of interprofessional education in pain at the time.

There are examples of good pain education, a specific pain management module for undergraduates at the University of Leeds and our own Interprofessional Pain Management Learning Unit at King’s College London. This was the first of its kind in the UK and was introduced three years ago. From six disciplines, 1300 students from dentistry, medicine, midwifery, nursing, pharmacy and physiotherapy study together using e-learning materials, online networking and workshops to enhance their knowledge and rehearse communication, interprofessional and clinical skills needed for practice.

In 2014, the British Pain Society Pain Education Special Interest Group, a national interprofessional group, will launch a campaign to improve pain education for pre-registration students across the healthcare disciplines. This will include the publication of a practical guide for universities to implement changes in the curriculum and increase the hours and variety of teaching and learning in pain education.

Postgraduate development in nursing

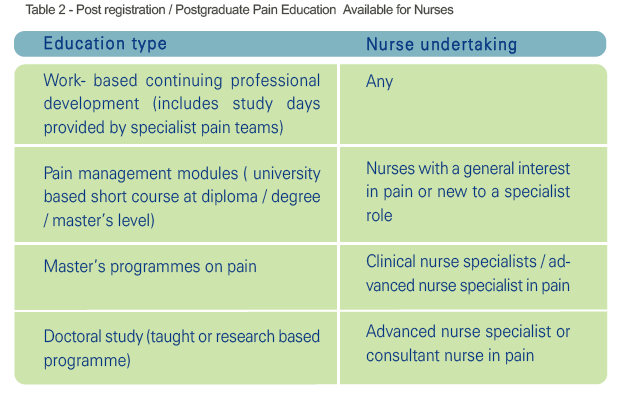

There are over 670,000 nurses and midwives registered in the UK working in a variety of community and hospital settings. Opportunities for pain education exist for this group and these are summarised in Table 2. For the majority, study days or short teaching sessions on pain management may be provided by local specialist pain teams. These are usually hospital-based although increasingly pain services and staff education can be based in the community and some organisations have made pain education part of the mandatory training for all staff.

Access to pain education can be problematic and there may be real barriers to continuing professional development. These include:

- Time – arranging study leave can be difficult in areas with lower staffing levels

- Funding – can be difficult to secure for external courses

- Access – restricted access to electronic sources of education because of funding

- Travel – universities may be some distance away for learners.

The British Pain Society and Faculty of Pain Medicine have recently launched a new e-learning course as part of the E learning for Health programme, a Department of Health initiative for staff working in the National Health Service (NHS). The national programme covers a variety of topics and the pain specific course is called E-Pain (11). This course is free to NHS staff may help to overcome some of the barriers to pain education.

Specialists in pain management

Nurses who specialise in pain are referred to as clinical nurse specialists and more senior roles of advance nurse specialist or nurse consultant. These are autonomous roles working within or leading a specialist pain team. The UK’s Department of Health (12) have published a position statement on the definition of advanced level nursing, a benchmark that includes 28 elements of practice under four themes:

- clinical/direct care practice

- leadership and collaborative practice

- improving quality and developing practice and

- developing self and others

Advanced level nurses are also required to have a Masters level education and nurse consultants split their time contributing to education, research and practice (for at least 50%).

Over the past decade the UK has been developing a programme for non-medical prescribers to improve access to medication for patients. Nurses, pharmacist, physiotherapists and paramedics are able to undertake a further academic study to allow them to prescribe either independently or as a supplementary prescriber where the diagnosis has been made by the he patient’s doctor and a clinical management plan agreed. A survey of specialist nurses working pain services (13) found that nurses are working over inpatient and outpatient services for pain and prescribing on average 19.5 times a week. They also contribute to local protocols on pain prescribing and are providing staff training, patient education and audit and research.

Networks available and national developments for nurses

Pain management networks in the UK provide an essential source of support and method of sharing practice for those with a general or specialist interest in pain. The Royal College of Nursing (RCN) is a professional body and union that represents nurses and promote individual and practice development. The RCN Pain and Palliative Care Forum is one of several forums within the RCN and has 14,000 members. Chaired by Felicia Cox, the forum has a steering committee and activities have included national study days, conference debates and a recent roundtable discussion with nursing leaders in the field of pain management. The meeting took place in November 2013 and the group are now working on three key areas; consolidating the evidence demonstrating the need for change, pain education and pain in vulnerable groups.

The RCN Pain and Palliative Care Forum also have regional groups such as the RCN London Pain Interest Group. This group (chaired by the author, EB) is a group of nurse specialists and meets four times a year to discuss practice changes and provide professional development opportunities such as complex case reviews and educational sessions. An effective email network also keeps people in touch throughout the year.

Organisations such as the British Pain Society, European Pain Fedderation EFIC and the International Association for the Study of Pain also provide an important network for specialist nurses in pain along with a wide range of development opportunities through study days, conferences and special interest groups.

Summary

The importance of pain education has been recognised and there are positive changes being made at local and national levels. For preregistration nurses, we need to focus on strengthening the Nursing and Midwifery Council standards that universities use to design their nursing programmes. Supporting universities to implement changes and make pain a higher priority is also key to address the growing number of people who are experiencing pain and reduce its impact. At a post-registration level, there are a number of opportunities for professional development around pain but many experience barriers such as time and funding which hinders the access to education. Focusing on reducing those barriers would mean that our workforce would be better prepared to manage complexities of pain for patients. Specialist nurses are playing a central role in practice development around pain management in their organisations and this needs to be continued to be supported.

Nurses have a unique relationship with patients but the education and practice issues raised here may not be unique to nursing. Our strengths is in the ability to work interprofessionally and there is strength in numbers. We need to use all our networks, all of our links with organisations that have an interest in pain education, to influence change; to beneift nurses, to benefit other healthcare professionals but ultimately, to benefit patients in pain.

References

1. Bridges S. Chronic Pain. Health Survey England 2011.London, Health and Social Care Information Centre, 2012. Available from https://catalogue.ic.nhs.uk/publications/public-health/surveys/heal-surv-eng-2011/HSE2011-Ch9-Chronic-Pain.pdf

2. Royal College of Nursing. The Recognition and Assessment of Acute Pain in Children (Second Edition). London, RCN, 2009. Available online: http://www.rcn.org.uk/development/practice/clinicalguidelines/pain

3. British Pain Society Cancer Pain Management. London, BPS, 2010. Available from http://www.britishpainsociety.org/pub_professional.htm#cancerpain

4. Patient’s Association. Public Attitudes to Pain. London, Patient’s Association, 2009. Available from: http://www.patients-association.com/Portals/0/Public/Files/Research%20Publications/PUBLIC%20ATTITUDES%20TO%20PAIN.pdf

5. Donaldson L. 150 years of the Annual Report of the Chief Medical Officer: On the State of the Public Health. London, Department of Health, 2009. Available from: http://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/20130107105354/http://www.dh.gov.uk/en/Publicationsandstatistics/Publications/AnnualReports/DH_096206

6. Nursing and Midwifery Council. Standards of proficiency for pre-registration nurse education. 2010. London: Nursing and Midwifery Council, 2010. Available from: http://www.nmc-uk.org/Educators/Standards-for-education/

7. Briggs E, Carr E, Whittaker M. Survey of undergraduate pain curricula for healthcare professionals in the United Kingdom. European Journal of Pain 2011;15 (8):789-795.

8. Ramsden P. Learning to Teach in Higher Education. London, Routledge Falmer, 2003.

9. Centre for the Advancement of Interprofessional Education. Defining IPE. London: CAIPE 2002 http://www.caipe.org.uk/about-us/defining-ipe/

10. Wilhelmsson M, Pelling S, Ludvigsson J, Hammar M, Dahlgren L, Faresjö T. Twenty years experiences of interprofessional education in Linköping – ground-breaking and sustainable. Journal of Interprofessional Care 2009; 23(2):121-33.

11. Faculty of Pain Medicine & British Pain Society. E-Pain. E-learning for Health Programme, 2013. Available http://www.e-lfh.org.uk/projects/pain-management/

12. Department of Health. Advanced Level Nursing: A position Statement. London, Department of Health, 2010. Available https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/215935/dh_121738.pdf

13. Stenner KL, Courtenay M, Cannons, K. Nurse prescribing for inpatient pain in the United Kingdom: A national questionnaire survey. International Journal of Nursing Studies 2011; 48(7):847-855.